Democracy in Southeast Asia: Made Difficult by Ethnicity and Religion?

- rebtanse

- Dec 2, 2022

- 12 min read

Rebecca SE Tan Originally written on 2 November 2021

Posted on 2 December 2022 Posting another one of my past writings :D It's nice to see how my writing style, especially in terms of headings, has changed in just one year!

Introduction

Southeast Asia (SEA) is fraught with numerous ethnicities and religions. These differences are perpetually emphasised by leaders to solidify their power bases and justify their hold on executive power, hence making democratisation difficult. However, I argue that the faultlines of ethnicity and religion are mere manifestations of colonial rule, which has complicated progress towards democratisation. In this essay, I specifically focus on Myanmar and Malaysia, although the arguments made are largely relevant to the whole of SEA.

National Identity Defined along Ethnic and Religious Lines

In SEA, national identity is often defined[1] along specific ethnic and religious lines. These lines are delineated, perpetuated, and exploited by state leaders. Under the guise of ‘protection’, leaders justify their use of executive power to reduce contestations to their rule.

‘Protecting’ the majority

With a national identity tied with ethnicity and religion, state leaders are able to fuel conflicts between ethnoreligious groups to consolidate power. Myanmar is one such example, where its national identity is defined in relation to the taingyintha[2] and a Buddhist core (Bakali & Wasty, 2020). Since the 1962 military coup, the taingyintha has even preceded citizenship (Cheesman, 2017), such that other ethnoreligious groups can even be perceived as a threat to the nation. By creating a ‘common enemy’, state leaders perpetuate their rule by portraying themselves as protectors and redirecting the anger of the public.

A. Portraying themselves as protectors

Myanmar’s leaders portray themselves as righteous protectors of Myanmar and Buddhism by depicting the Muslim minority as both a ‘faith enemy’ and a ‘security threat’ (Rowand & Artinger, 2021; Schissler et al., 2017). Both the military government and the civilian government has pushed such a narrative (Dussich, 2018), such as postulating that Muslims will use citizenship privileges to convert Burmese forcibly or framing attacks on Muslims as a ‘global war on terror’ (Bakali, 2021; The Guardian, 2017). By demonising Islam, the populace adopts a ‘survival mindset’, which boosts the legitimacy of the leaders (Hre, 2013).

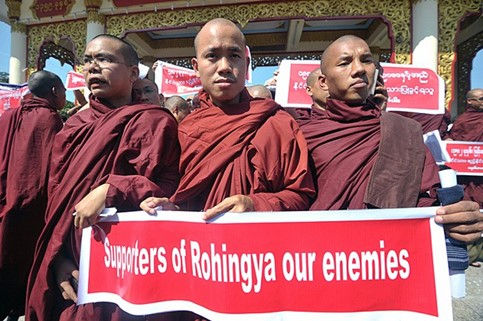

This strategy is particularly effective when endorsed by monks, seen as symbols of Buddhism. For example, monastic leader Ashin U Wirathu openly supports the military and refers to mosques as ‘enemy bases’, as he believes that weakness will lead their land to become Muslim (Fuller, 2013; Klinken & Aung, 2017). Other Buddhist monks have also condemned the Muslim-majority Rohingya for their perceived terrorist tendencies (Prasse-Freeman, 2017). Such support further provides religious and cultural grounds to justify a leaders’ executive power.

Role of Buddhist monks in bolstering the leaders’ legitimacy (RFA, 2016).

B. Redirecting the anger of the masses

State leaders are also able to effectively redirect the anger of the masses to the ethnic and religious minorities, distracting citizens from their failings. For example, this scapegoating tactic has been used with great consequences for the Rohingya (Klinken & Aung, 2017), an ethnoreligious minority in Myanmar. The Rohingya are different from the majority on three accounts – they speak Rohingyan rather than Burmese (Mithun, 2018), are primarily Muslim instead of Buddhists (Ibrahim, 2018), and generally have a darker skin tone (Akhter & Kusakabe, 2014). As such, Buddhist extremists have targeted this group with anti-Muslim campaigns and violence (Bakali, 2021).

This ethnoreligious divide is supported by Myanmar’s leaders. Despite being indigenous to Western Myanmar, state leaders have claimed that the Rohingya are not a part of the “national races” and even postulate that they are illegal immigrants from Bangladesh (Azad & Jasmin, 2013). Without citizenship, the Rohingya find themselves denied basic rights, such as voting, access to services and education, and even the freedom of movement (Dussich, 2018; Maizland, 2021). State leaders routinely ignore the plight of the Rohingya, granting no justice to those who were displaced, raped, or killed (Frontières, 2018). Military leaders have also enacted repressive laws and released the anti-Muslim monk, Wirathu, from jail (Aljazeera, 2021; Wade, 2017).

Through this divide, leaders perpetuate their regime by convincing citizens that problems of the nation – such as the poor standard of living or the brutalness of the military regime – is the Rohingya’s fault alone (Bakali & Wasty, 2020). Ironically, the precarious position of the Rohingya deters them from challenging the state, as they attempt to insist on their taingyintha status and ‘prove’ their potential as good citizens (Cheesman, 2017; Thawnghmung, 2016).

C. Other SEA Countries

Marginalising ethnoreligious minorities as a means to justify executive power is not unique to Myanmar. In Thailand and Malaysia, one’s national identity is also intricately linked with religion and ethnicity. This conflation of identity becomes easy quarries for ethnoreligious politicking, such as through the marginalisation of the Muslims in Thailand and the Chinese in Malaysia. As such, calling for a relinquishment of executive power may be deemed traitorous to one’s ethnoreligious identity, as the state’s power is perceived as a protection against minorities.

‘Protecting’ the minority

Nation leaders may also invoke the “protection” of ethnoreligious minorities to justify their repressive laws. These laws can be used to keep dissenters and political opposition in check while being particularly hard to challenge due to their legal nature.

A noteworthy example is Malaysia’s arsenal of draconian laws. After the racial riot of 1969, the state has emphasised the need for ethnoreligious harmony[3] (Muis et al., 2012). While this goal is noble, leaders have abused it to justify political repression as well. Framed as 'democratically passed' laws to prevent ethnoreligious conflict, draconian laws are able to limit public discourse under the pretence of protecting minorities (Barraclough, 1985; Sani, 2008). These laws, such as the Internal Security Act (ISA) and the Sedition Act (SA), are harsh and broadly defined, giving the government undue power to cripple political opponents and bulldoze political activism (HRW, 2015).

One such victim is the Democratic Action Party (DAP), which has taken several hits for raising ‘sensitive issues’ (Barraclough, 1985). Following the 1969 racial riot, DAP Secretary-General Lim Kit Siang was detained under ISA for its instigation, despite not having been in Peninsular Malaysia at the time (Munro-Kua, 1996). Again in 1971, DAP parliamentarian Fan Yew Teng was prosecuted under SA for alleging that United Malays National Organisation (UMNO) was racially discriminatory in some sectors (Sani, 2008). Found guilty, Fan Yew Teng was fined, imprisoned, and lost his parliamentary seat (Sani, 2010). As seen, threats to the government’s rule can be easily removed through the guise of upholding ethnoreligious security.

Draconian laws are also able to shut down political activism and democratic discourse. In response to the 1974 demonstration by student organisations, the government used the ISA to detain prominent activists, such as Anwar Ibrahim (Funston, 1999). These harsh measures decimated student-led political activism and served as a warning against expressing dissent.

Furthermore, these laws to ‘maintain religious harmony’ are not consistent with the leaders’ use of ethnic and religious sentiments to gain votes. During the power struggle of 1987, UMNO allegedly triggered ethnic polarisation to justify their draconian measures and consolidate power (Lee, 2014). Again in 2013 and 2018, UMNO stoked pro-Malay and pro-Islam sentiments to retain or gain back its rule (Welsh, 2020). By fanning racial tensions themselves, the leaders demonstrate that the narrative of protecting minorities is a mere façade for their true intentions.

This tactic is no stranger to SEA. Other competitive authoritarian regimes such as Singapore, Cambodia, Thailand, and the Philippines have their own sets of laws that grant the ruling party undue power and influence while maintaining a façade of democracy (Curato & Fossati, 2020).

Ethnoreligious Divisions as an Aftereffect of Colonialism

While ethnicity and religion are the most apparent factors, the lack of democratisation in SEA cannot be fully attributed to these factors. I argue instead that colonialism, which brought along primordial definitions of ethnicity and religion, paved the way for leaders today to utilise ethnoreligious faultlines for their purposes. Seen from a historical institutionalism lens, the colonisation of SEA countries has set them on a trajectory decidedly away from democratisation, making it challenging to ‘correct’ its course.

Primordial definitions of ethnicity and religion

Colonialists spread their worldviews to their colonies, often including their primordial definition of ethnicity and religion. In this view, ethnicity is immutable and biologically determined, while religion is an irreconcilable difference in people (Mahmud, 1999). The idea that religion and ethnicity rigidly define your identity and loyalties has manifested itself in the focus of taingyintha in Myanmar and the ethnoreligious-based narratives in Malaysia.

The Conflation of Taingyintha with Citizenship

In colonial Burma, the British employed a physiognomy-based[4] logic and a ‘divide and rule’ approach (International Crisis Group, 2020; Prasse-Freeman, 2017). Following this, colonialists gave more military, economic and administration opportunities to certain ethnoreligious groups (Taylor, 1981), such as the Chinese, the South Asians, and the Muslims (Crouch, 2016; Prasse-Freeman, 2017). This unfairness hence laid the foundation for the paramount importance placed on one's ethnoreligious identity today.

To complicate matters, these ethnoreligious faultlines were further infixed in the fight for independence. During World War II, the Rohingya Muslims fought alongside the British against the Japanese, as the British had promised them land and autonomy (Mithun, 2018). The British later reneged on their promise and rejected their following request to become part of Pakistan (Chan, 2005). Burmans viewed this alliance and subsequent attempt of separation as a betrayal, as they wanted to unite against the colonial threat (Foxeus, 2019). In addition, rallying calls against colonialism, such as 'Burma for the Burmans[5]' and "To be Burman is to be Buddhist", further alienated minority ethnoreligious groups (Mazumder, 2013; Walton, 2013).

As such, ethnicity and religion became important prerequisites to be part of the ‘imagined community’ (Anderson, 1991; Walton, 2013). Other ethnic or religious groups are seen as fundamentally different and threatening to the Bamar Buddhist majority (Wade, 2017). With this rigid perspective ingrained in the minds of Myanmar today, leaders are able to rile up ethnoreligious sentiments to justify their abuse of power.

Differences and How to Deal with Them

In colonial Malaysia, the primordial definitions of ethnicity and religion took root in a different form. Colonials had spread the myth that natives, who were primarily Malay and Muslim, were ‘indolent, dull, backward and treacherous’, because they had refused to submit to the unfair terms set by the British (Alatas, 2010, p.8). By contrast, the Chinese and Indian migrants had no such choice, given their poor living conditions back home. The colonialists then framed this disparity in industriousness as a consequence of one’s ethnicity and religion (Gorer, 1936). As such, ethnicity and religion became significant cleavages[6] within the population and are used as justifications for coercive measures today.

Additionally, Malaysia also inherited the rationale and methodology colonials used to deal with differences. Since differences were seen as immutable and dangerous, colonials ruthlessly used coercion to eliminate ‘threats’. Justified then as a means to quell the threat of Communism and radical Malay nationalism (Barraclough, 1985), colonials have inadvertently passed on their coercive mechanisms to independent Malaysia, giving leaders today the power to decimate their opponents and dissenters.

Other SEA countries

All SEA countries have been impacted by colonialism through its spread of beliefs, systems, and demarcation of borders[7]. Hence, the way colonialists defined ethnicity and religion sheds light on the state of SEA countries today. When defined as irreconcilable differences, these identities become sources of tensions that leaders exploit to justify their undue executive power.

The effect of colonialism becomes especially poignant when comparing the examples of Malaysia and Myanmar to that of Indonesia. While Indonesia is even more ethnically and religiously diverse (Pedersen, 2016), colonialism had not emphasised these identities, leading to a more democratic outcome today. Under the Dutch administration, Indonesia was unified by the use of Malay, vernacular media, and the People’s Council (Henley, 1995). Hence, shared values[8], rather than the stoking of ethnoreligious sentiments, were used to garner support for independence (Henley, 1995). In fact, despite having a Muslim majority, it is the Islamic groups[9] who have been pushing to expand civil society, protect ethnoreligious minorities and defend pluralism (Walden, 2016). While Indonesia’s democracy may not be perfect, its integrative form of nationalism has led to more inclusive outcomes, such as the endorsement of religious groups and the greater diversity of the cabinets (Aspinall, 2015).

Conclusion

While ethnoreligious faultlines make democratisation more difficult to achieve in SEA, delving into how those faultlines were created and defined through colonialism gives us a more nuanced understanding of SEA countries today. This proposition, perhaps, is a source of optimism. While ethnic and religious differences are likely here to stay, the scars that colonialism left may, through much effort, slowly be erased away.

[1] Or, socially constructed (Anderson, 1991) [2] National races, as defined by the state (Cheesman, 2017) [3] See: the Rukun Negara (National Principles) of Malaysia [4] Belief that physical features correspond to psychological characteristics (Chowdhory & Mohanty, 2020). [5] Includes some other indigenous groups of Burma besides the majority ethnic Burmans [6] For example, Bumiputera policies that favour Malays and Muslims cause tensions and alienation of other ethnoreligious groups. [7] All SEA countries were colonised except for Thailand. Even then, Thailand inadvertently had its borders defined by the colonials of surrounding countries, leading to stark contrasts of identities between the majority Buddhist Thais and the minority Malay Muslims in Southern Thailand. [8] The Pancasila [9] For example, the Nahdlatul Ulama advocates for Islam Nusantara, a tolerant form of Indonesian Islam (Walden, 2016)

References

Akhter, S., & Kusakabe, K. (2014). Gender-based Violence among Documented Rohingya Refugees in Bangladesh. Indian Journal of Gender Studies, 21(2), 225–246. https://doi.org/10.1177/0971521514525088

Alatas, S. H. (2010). The myth of the lazy native : a study of the image of the Malays, Filipinos and Javanese from the 16th to the 20th century and its function in the ideology of colonial capitalism. Routledge.

Aljazeera. (2021, February 7). Myanmar military frees Wirathu, notorious anti-Muslim monk. Www.aljazeera.com. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/9/7/myanmar-military-frees-wirathu-notorious-anti-muslim-monk

Anderson, B. (1991). Imagined Communities : Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. Verso.

Aspinall, E. (2015). The Surprising Democratic Behemoth: Indonesia in Comparative Asian Perspective. The Journal of Asian Studies, 74(4), 889–902. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0021911815001138

Azad, A., & Jasmin, F. (2013). Durable Solutions to the Protracted Refugee Situation: the Case of Rohingyas in Bangladesh. Journal of Indian Research, 1(4). https://www.academia.edu/5886047/Durable_Solutions_to_the_Protracted_Refugee_Situation_the_Case_of_Rohingyas_in_Bangladesh

Bakali, N. (2021). Islamophobia in Myanmar: the Rohingya genocide and the “war on terror.” Race & Class. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306396820977753

Bakali, N., & Wasty, S. (2020). Identity, social mobility, and trauma: Post-Conflict educational realities for survivors of the rohingya genocide. Religions, 11(5), 241. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11050241

Barraclough, S. (1985). The Dynamics of Coercion in the Malaysian Political Process. Modern Asian Studies, 19(4), 797–822. https://www.jstor.org/stable/312459

Chan, A. (2005). The Development of a Muslim Enclave in Arakan (Rakhine) State of Burma (Myanmar) 1. AYE CHAN SOAS Bulletin of Burma Research, 3(2). https://www.soas.ac.uk/sbbr/editions/file64388.pdf

Cheesman, N. (2017). How in myanmar “national races” came to surpass citizenship and exclude rohingya. Journal of Contemporary Asia, 47(3), 461–483. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472336.2017.1297476

Chowdhory, N., & Mohanty, B. (Eds.). (2020). Citizenship, Nationalism and Refugeehood of Rohingyas in Southern Asia. Springer Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-2168-3

Crouch, M. (2016). Islam and the state in Myanmar : Muslim-Buddhist relations and the politics of belonging. Oxford University Press.

Curato, N., & Fossati, D. (2020). Authoritarian innovations. Democratization, 27(6), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2020.1777985

Dussich, J. P. J. (2018). The Ongoing Genocidal Crisis of the Rohingya Minority in Myanmar. Journal of Victimology and Victim Justice, 1(1), 4–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/2516606918764998

Foxeus, N. (2019). The Buddha was a devoted nationalist: Buddhist nationalism, ressentiment, and defending Buddhism in Myanmar. Religion, 49(4), 661–690. https://doi.org/10.1080/0048721x.2019.1610810

Frontières, M. S. (2018). No one was left: death and violence against the Rohingya in Rakhine state, Myanmar. Nyu.edu. https://doi.org/http://hdl.handle.net/2451/42262

Fuller, T. (2013, June 20). Extremism Rises Among Myanmar Buddhists. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2013/06/21/world/asia/extremism-rises-among-myanmar-buddhists-wary-of-muslim-minority.html

Funston, J. (1999). MALAYSIA: A Fateful September. Southeast Asian Affairs, 165–184. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27912226

Gorer, G. (1936). Bali and Angkor. Michael Joseph.

Henley, D. E. F. (1995). Ethnogeographic Integration and Exclusion in Anticolonial Nationalism: Indonesia and Indochina. Comparative Studies in Society and History, 37(2), 286–324. http://www.jstor.com/stable/179283

Hre, M. (2013). Religion: A Tool of Dictators to Cleanse Ethnic Minority in Myanmar? IAFOR Journal of Ethics, Religion & Philosophy, 1(1). https://doi.org/10.22492/ijerp.1.1.02

Human Rights Watch. (2015, October 26). Creating a Culture of Fear: The Criminalization of Peaceful Expression in Malaysia. Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/report/2015/10/27/creating-culture-fear/criminalization-peaceful-expression-malaysia

Ibrahim, A. (2018). The Rohingyas : inside Myanmar’s hidden genocide. Hurst & Company.

International Crisis Group. (2020, August 27). Identity Crisis: Ethnicity and Conflict in Myanmar. Crisis Group. https://www.crisisgroup.org/asia/south-east-asia/myanmar/312-identity-crisis-ethnicity-and-conflict-myanmar

Klinken, G. van, & Aung, S. M. T. (2017). The Contentious Politics of Anti-Muslim Scapegoating in Myanmar. Journal of Contemporary Asia, 47(3), 353–375. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472336.2017.1293133

Lee, J. C. H. (2014). Multiculturalism and Malaysia’s (Semi-) Democracy: Movements for Electoral Reform in an Evolving Ethno-Political Landscape (N.-K. Kim, Ed.). Springer Link; Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1057%2F9781137403452_5

Mahmud, T. (1999). Colonialism and modern construction of race : a preliminary inquiry. University Of Miami, School Of Law.

Maizland, L. (2021, February 9). Myanmar’s Troubled History: Coups, Military Rule, and Ethnic Conflict. Council on Foreign Relations. https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/myanmar-history-coup-military-rule-ethnic-conflict-rohingya

Mazumder, R. (2013). Constructing the Indian Immigrant to Colonial Burma, 1885-1948. Escholarship.org. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/24c1m8gj

Mithun, M. B. (2018). Ethnic Conflict and Violence in Myanmar: The Exodus of Stateless Rohingya People. International Journal on Minority and Group Rights. https://doi.org/10.1163/15718115-02504003

Muis, M. A., Mohamed, B. A., Rahman, A. A., Zakaria, Z., Noordin, N., Nordin, J., & Yaacob, M. A. (2012). Ethnic Plurality and Nation Building Process: A Comparative Analysis between Rukun Negara, Bangsa Malaysia and 1Malaysia Concepts as Nation Building Programs in Malaysia. Asian Social Science, 8(13). https://doi.org/10.5539/ass.v8n13p153

Munro-Kua, A. (1996). Authoritarian Populism in Malaysia. London Palgrave Macmillan Uk.

Pedersen, L. (2016). Religious Pluralism in Indonesia. The Asia Pacific Journal of Anthropology, 17(5), 387–398. https://doi.org/10.1080/14442213.2016.1218534

Prasse-Freeman, E. (2017). The Rohingya crisis. Anthropology Today, 33(6), 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8322.12389

Radio Free Asia. (2016, June 21). Myanmar Government Orders State Media Not To Use “Rohingya.” Radio Free Asia. https://www.rfa.org/english/news/myanmar/myanmar-government-orders-state-media-not-to-use-rohingya-06212016155743.html

Rowand, M., & Artinger, B. (2021, February 16). When buddhists back the army. Foreign Policy. https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/02/16/myanmar-rohingya-coup-buddhists-protest/

Sani, M. A. M. (2008). Media freedom and legislation in Malaysia. Journal of Ethics, Legal and Governance, 4, 69–86. http://repo.uum.edu.my/id/eprint/11935

Sani, Mohd. A. Mohd. (2010). Dynamic of ethnic relations in Southeast Asia (R. Nakamura & S. L. Taya, Eds.). Newcastle Upon Tyne Cambridge Scholars.

Schissler, M., Walton, M. J., & Thi, P. P. (2017). Reconciling Contradictions: Buddhist-Muslim Violence, Narrative Making and Memory in Myanmar. Journal of Contemporary Asia, 47(3), 376–395. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472336.2017.1290818

Taylor, R. H. (1981). Party, class and power in British Burma. The Journal of Commonwealth & Comparative Politics, 19(1), 44–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/14662048108447373

Thawnghmung, A. M. (2016). The politics of indigeneity in Myanmar: competing narratives in Rakhine state. Asian Ethnicity, 17(4), 527–547. https://doi.org/10.1080/14631369.2016.1179096

The Guardian. (2017, September 6). Aung San Suu Kyi says “terrorists” are misinforming world about Myanmar violence. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/sep/06/aung-san-suu-kyi-blames-terrorists-for-misinformation-about-myanmar-violence

Wade, F. (2017). Myanmar’s enemy within : Buddhist violence and the making of a Muslim “other.” Zed Books Ltd.

Walden, M. (2016, December 1). Islamic civil society’s enduring vitality in Indonesia’s democracy. Www.lowyinstitute.org. https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/islamic-civil-societys-enduring-vitality-indonesias-democracy

Walton, M. J. (2013). The “Wages of Burman-ness:” Ethnicity and Burman Privilege in Contemporary Myanmar. Journal of Contemporary Asia, 43(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472336.2012.730892

Welsh, B. (2020, August 18). Malaysia’s Political Polarization: Race, Religion, and Reform - Political Polarization in South and Southeast Asia: Old Divisions, New Dangers. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. https://carnegieendowment.org/2020/08/18/malaysia-s-political-polarization-race-religion-and-reform-pub-82436

.png)

Comments